If you’ve been a long-time reader of my newsletters, you’ll know that every once in a while (usually during the spring) I go completely off topic with a story that I’ve written that is offtopic for photography. The last one I shared was You Don’t Have to Sleep in Your Car. That was three years ago. I write a lot of these that sit on my hard drive and never get shared.

Throughout my life, I’ve never considered myself one thing — I’m not just a photographer or a writer or a canoeist or a kayaker or a watercolorist or an artist or a backpacker or a bicyclist. Like everyone I have a lot of interests and occasionally I like to share my other interests (I’m actually mystified and completely impressed by people who have a singular focus). Anyway, I believe that to be better artists we must be in the world and photograph the world from that perspective. That makes it healthy to explore other interests. It’s a must for me.

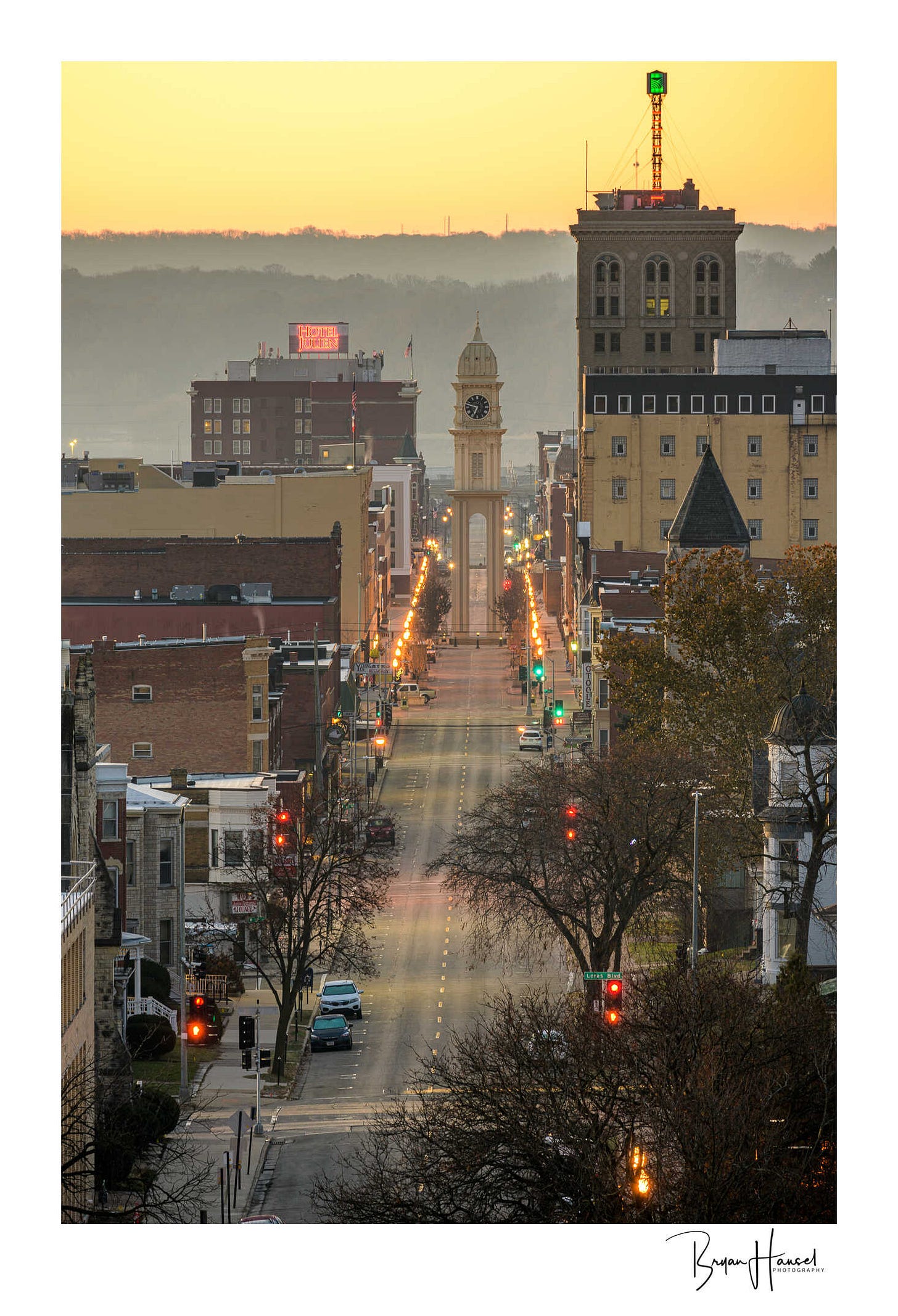

So, here’s a story I wrote about eagles and the town I grew up in. It’ll have photos from Iowa in it, too.

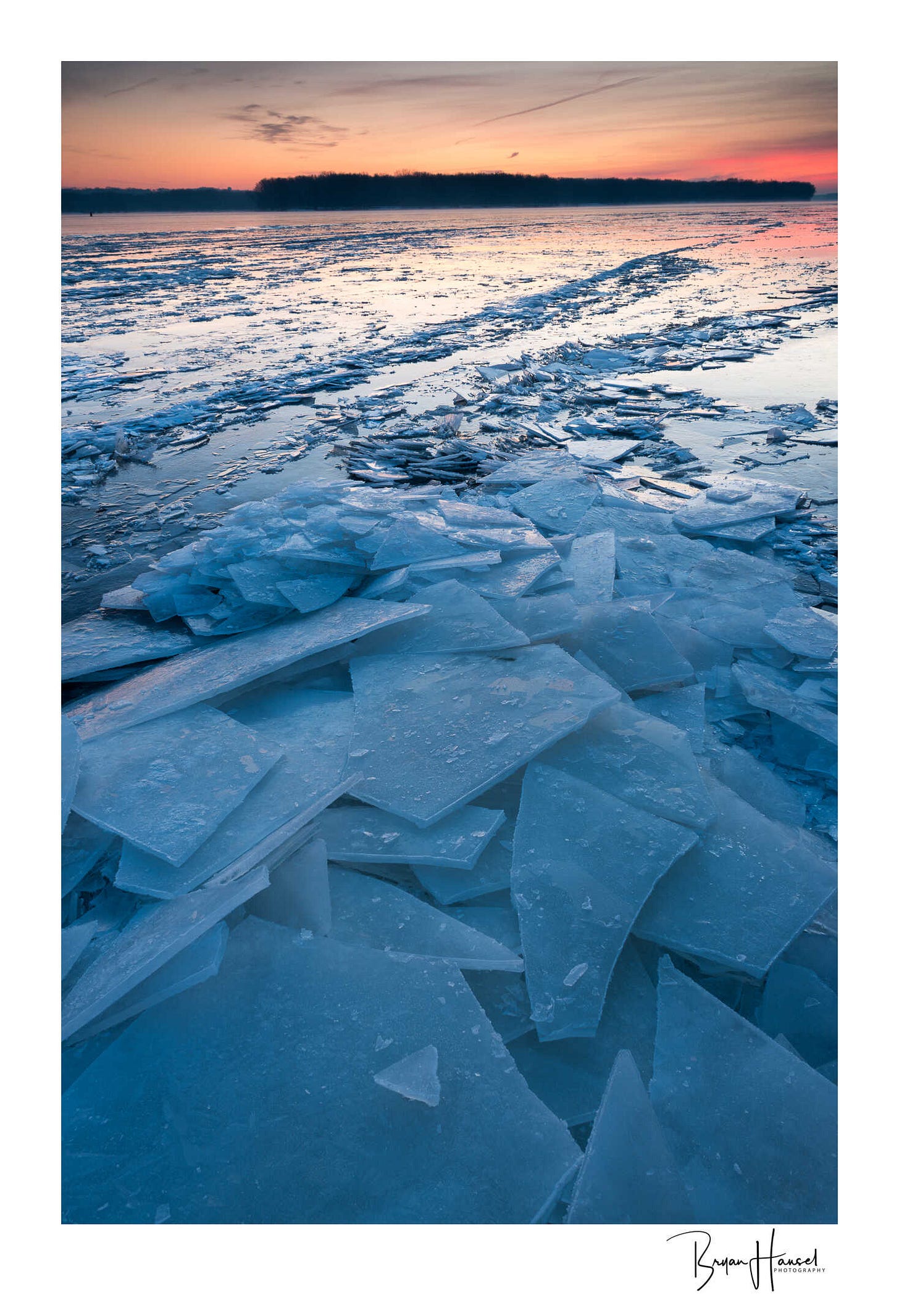

When I was a kid, bald eagles were rare. Every winter, my parents took us down to Lock and Dam #11 on the Mississippi River hoping to see a migrating bald eagle. If we saw one, it was a great day. If we saw two, it was amazing. To put it into perspective with numbers, when I was 10 there were only 1,188 mating pairs of bald eagles. That was all of them. Seeing one was a winter priority, because it was the only time that they’d be in the area.

The Lock and Dam was a good place to see eagles. While the rest of the Mississippi River would freeze up, the churning water coming out of the open dam gates would eat the ice and leave ice-free pools where an eagle could fish, land on the ice and then tear into its fresh catch while spilling a stain of red on the white ice.

Growing up in Dubuque, we went down to Lock and Dam #11 often. In the summer, we’d watch the slow walk of barges locking up and down the river. Back then, you could walk the grounds and explore the awe-inspiring buildings from the 1930s when America was flexing its power and the government buildings reflected the grandeur Americans felt. Inside the main building, the air felt cold even in the summer. The floor was a dark tile, and the walls were dark in color. The ceiling arched overhead resting on rows of windows, and interpretive displays lined the walls. You’d talk almost in a hushed-library whisper not only because the room echoed every word loudly, but because it felt like you were standing under the weight of history and under all the American might required to attempt to tame the Big Muddy.

The buildings and grounds weren’t the only awe-inspiring feature in the area; the 100-foot limestone cliffs of Dubuque’s Eagle Point Park formed a backdrop for the lock and dam. As a kid, it felt dizzying to look up at the fence on the cliff’s edge where people used coin-operated tower viewers to look down upon the lock and dam.

In what always seemed like an ironic name to me as a kid due to the lack of eagles, Eagle Point Park was a staple of our childhood and the crown jewel of Dubuque. No other location in the town, other than Julien Dubuque’s castle-like tower grave, drew as many people. Back in 1908, when nearly 100,000 matting pairs of bald eagles lived in the country, Dubuque established Eagle Point Park in response to an insult given by a Virginian. This was just 38 years after Virginia was admitted back into the Union, and because Dubuque mined and refined lead into shot for the Union Army, you can imagine the insult carried weight.

In 1907, Charles M. Robinson, one of Virginia’s most prolific architects of the time, visited Dubuque and said, "I have never seen a place where the Almighty has done more and mankind less, than Dubuque." That was only four years after President Teddy Roosevelt while visiting the Grand Canyon said, “Leave it as it is. Man cannot improve on it; not a bit. The ages have been at work on it and man can only mar it.” The juxtaposition of the feelings about nature at the time and between these two men couldn’t have been greater. Dubuque went with Robinson and built the park.

It was a grand park with cement walkways, picnic pavilions, lots of picnic tables, a fish pool with foot-long goldfish, and the important part for a kid, it had playground equipment. Just after it opened the city built a streetcar route to help deliver Dubuquers to nature. By the 1930s, it needed upgrades to handle the traffic. The park superintendent used $200,000 to build new pavilions, gardens, and buildings in the style of Frank Lloyd Wright. It was also at this time that Eagle Point Park’s sand swimming beach on the Mississippi River was taken over and turned into Lock and Dam #11.

While I can think about the loss of that swimming beach and wonder if my great grandparents took my grandfather there as a kid, I can’t complain because that Lock and Dam let me see an eagle. Those eagles with their bald heads sitting alone on the edge of the ice gave me a lifelong appreciation for seeing bald eagles. The excitement of my dad when he’d see an eagle gave me more appreciation for those bald eagles than it having been the symbol of America since 1782.

As I grew up, the appreciation of the bald eagle spread to other animals. Deer, turkey, grouse, hawks, and quail were fun to find and see. They were all rare in my childhood. Seeing a deer was almost as exciting as seeing a bald eagle. Spotting a red-tailed hawk sitting on a fence post could provide joy for hours. But the eagle was the grail of sightings.

I remember one such sighting when my buddy Steve and I were hiking into a remote – as remote as you can get in Iowa – river valley. We were scouting for some riffles and whitewater that we heard were on the river. It was late winter but after what limited snow Iowa got after I had finished college had melted. The oak forest was open. There was no trail, but we knew that the river valley was over a bluff, and we knew that if we gained the bluff, we should be able to make out the entire section of the river.

As we hiked, I looked for wildlife in the oaks and their now-brown leaves which had hung on through the winter. Steve and I were also talking, and I lost track of things for a while. Then we hit the edge of the bluff. The river laid out before us and cut the valley into two. Oaks lined the bluff on our side of the river and oaks lined the bluff opposite us. Across the river from us, the biggest oak held two dozen bald eagles. I had never seen so many at once in my life. Stunned and excited, I watched them sit like statues only shifting their heads now and then. Two dozen eagles. I had never seen so many in my life.

Two dozen eagles.

To think that that was a lot. It's hard to imagine the plight of the eagle. From a 100,000 breeding pairs in the late 1800s, their population started to dwindle due to habitat loss and hunting. In 1940, a law protected the eagle from hunting and the capitalist bird market that thrived on dead eagle sales. Then DDT came into use and decimated the eagle population. Just 400 breeding pairs survived the DDT. Outlawing DDT, passing the Endangered Species Act and adding the bald eagle to the list, and 1000s of people working to restore the bald eagle worked. There are now over 70,000 breeding pairs.

I do wonder if the bald eagle hadn’t been the symbol of America would they would have survived. If that early American Congress hadn’t adopted a bird as the American symbol, bald eagles probably would have gone the way of the passenger pigeon. Industrialists would have claimed that protecting them would be too expensive or result in too much land being taken away from progress. Look at the battle over the sage grouse or the northern long eared bat and the arguments made by short-sighted men against protecting their habitat. Apply the arguments against protecting the sage grouse and the bat and adopt Ben Franklin’s view of the bald eagle to imagine what would have happened.

In 1784, Franklin penned a letter to his daughter proclaiming, “For my own part I wish the bald eagle had not been chosen as the representative of our country. He is a bird of bad moral character. He does not get his living honestly. You may have seen him perched on some dead tree, where, too lazy to fish for himself, he watches the labour of the fishing hawk; and when that diligent bird has at length taken a fish, and is bearing it to his nest for the support of his mate and young ones, the bald eagle pursues him, and takes it from him…”

Franklin didn’t like the bald eagle. If that view had been common in the mid-20th century, the bald eagle would be gone.

I’d have never seen one in my life.

My parents wouldn’t have taken me down to Lock and Dam #11 to look for bald eagles. I’d have never seen my dad’s excitement about seeing an eagle. I wouldn’t have shared my love of bald eagles to my kid, and last October, my kid would have never seen the bald eagle fly ahead of us down the Kawishiwi River for an entire day as we paddled a canoe deep into the Boundary Waters.

As mighty and grand as America might be – for as many Mississippi Rivers it might tame – for all the wars it survived – for all the parks and grandeurs that it built – the bald eagle, somehow against the odds, surviving us is our greatest accomplishment. I hope that in the future that bald eagles never become rare like they were back then. Next time, they might disappear.

Until next time

This issue is a little diversion from photography, but without photography I don’t think I’d have been able to tell this story. My photos helped illustrate my thoughts. The power of visual art is in part its ability to give words a deeper meaning.

I hope you enjoyed this issue. I’ll see you again in two weeks right before my busy spring travel schedule kicks into gear.

Bryan, this is great. I live in Dubuque now and it's fun to read your perspective as a like-minded person who grew up here. I'm actually heading up to Grand Marais next weekend for a few days of me-time and photo-making. While the weather isn't looking great maybe I will run into you out somewhere! I've got lots of Dubuque photos on Instagram if you ever get homesick (IG: will.hoyer)

Thanks for the nice diversion while sitting in my office this morning. I'm around your age (a little older I believe) and I share your amazement at seeing Bald Eagles in the wild. Growing up the only ones I ever saw were at the Cleveland Zoo. In the mid 1980's I saw one far off in the distance in Bar Harbor, Maine and was just awe struck. Years later on a trip back from Grand Marais (probably one of your workshops) I got to see two up close in northern Wisconsin and I was less than awe struck. Seeing these majestic birds picking at road kill sure put a dent in their image for me. Now, when I drive to downtown Columbus from my house on the road that follows the Scioto River, I pass a small parking lot that has, in the last few years, turned into the viewing spot for a nest just across the river. Birders and photographers are there pretty much every day watching this pair of eagles who have nested in this spot for the last ten years or so. Because of how rare these birds were when I was growing up I will never take them for granted and if I see one flying overhead I will just stop what I am doing and look up with a big smile on my face.