A quick aside before I get to this week’s essay. Public pressure on our senators worked, and the sale of your public lands was removed the GOP budget bill. This issue isn’t going away though. They will try this again. But let’s celebrate this win. Thank you for all you did to help prevent this sale. Now back to our regularly scheduled program.

The Man with Antlers on the Cliff

Late one fall, I slipped away for a solo canoe trip from Voyageurs National Park to Grand Portage along the border and through the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. I had two weeks to travel the old Voyageur Route, also known as the Border Route, which is approximately 200 miles long and followed the historic footprints of fur traders. I’d looked forward to the trip all year.

As if they wanted to celebrate the start of my adventure, the night before I left, the northern lights glowed green and swayed. They filled the sky to the north, south and overhead. They danced with passion. I had seen the northern lights before, but never like this. I stayed up nearly the entire night photographing them.

At one point during the night, I took a breather to glance through my photos and noticed that on the camera two bands of northern lights appeared to make two hands cupping each other in a sign of peace. I didn’t notice that with my eyes, but in the photo they were there. To me, the photo suggested supernatural forces at play in the northern lights.

As a photographer, I know that the mind can be fooled. We capture a slice of reality that creates whatever we want you to see. Were there really hands cupping each other in the northern lights? No, the camera captured that single moment in time when it looked that way. The bands quickly transformed into a different shape.

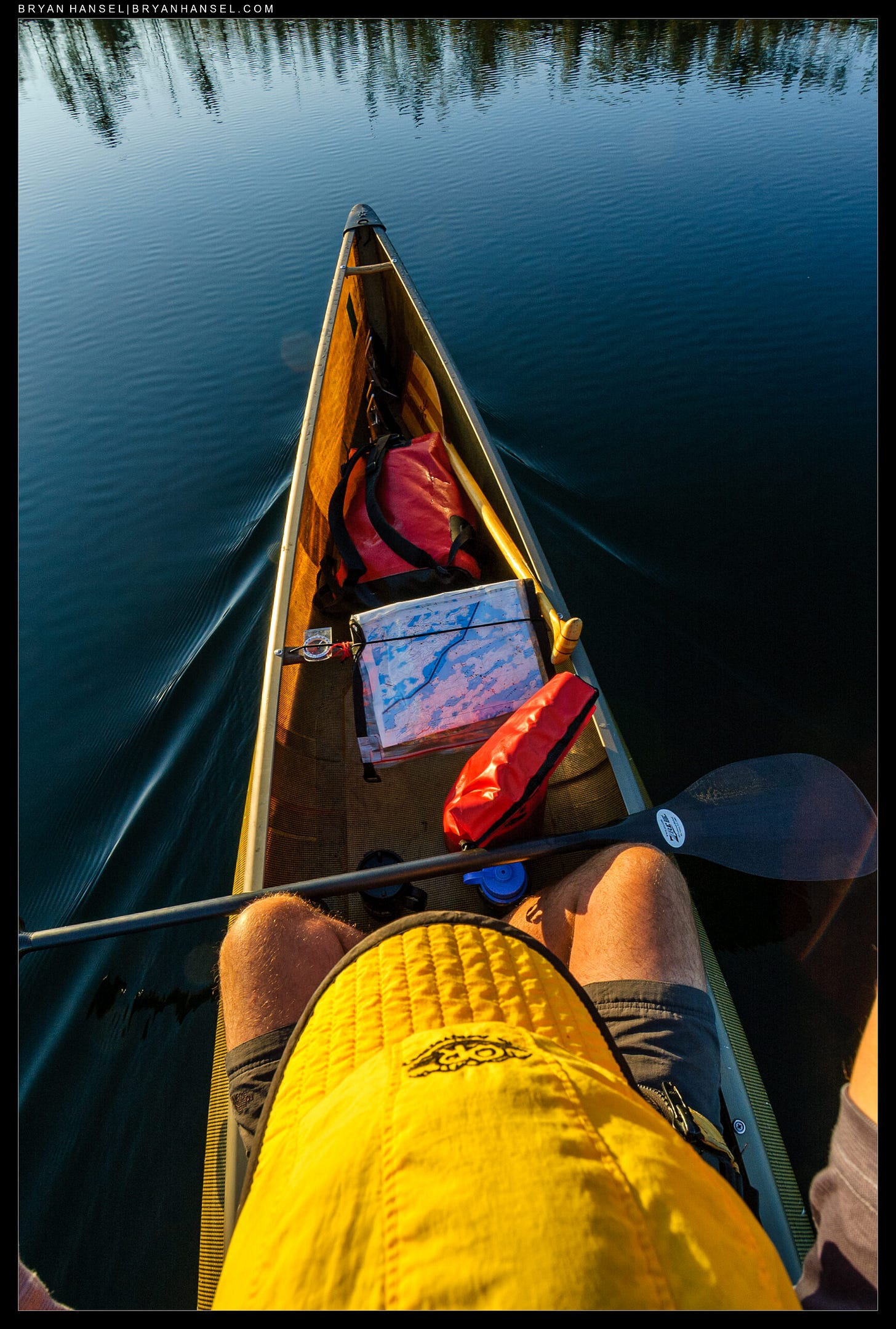

But, I took the northern lights event as a good sign, and the next day I pushed off into Crane Lake. The dip of my paddle and the drops of water falling from my paddle into the calm lake pulled me into the rhythm of the trip. I was off.

It wasn’t long before I passed Hangman’s Island, a rocky island where an eerie effigy of a hanging man was hanging from a dead, bark-stripped tree. For the rest of the day, I didn’t even want to contemplate the meaning or the history behind Hangman’s Island. Eventually, I found a campsite along a river. Lying under my tarp, I hid my head inside my sleeping bag as mosquitoes buzzed around.

What in the world did I get myself into, I thought.

In the past, I always looked at my solo fall canoe trips to find a greater connection to the environment and to understand the world better and to emerge from the wilderness with a changed outlook or perception and as a new man.

And on this one, I was hiding in my sleeping bag from late-season mosquitoes. What was I expecting? To commune with a romanticized 1950s or 60s version of wilderness and to emerge a wholly spiritual being. Instead, I was being grounded in the physical world by the buzz of mosquitoes trying to invade my space.

On day two, I passed wheeled railroad portages for motorboats and landed on Lac LaCroix. At camp that night on an island in the middle of islands with placid water calm as can be, the sunset turned the late-day fair weather cumulous clouds deep reds and oranges. It reflected perfectly across the water.

As the sun set above, it set below.

Red skies at night are a sailor’s delight. I thought, it’s funny how we carry these ancient sayings without questioning them, but this one sometimes works for the Boundary Waters. Many of the weather systems come from the west and pass to the east, so a red sky means that there’s a break in the clouds to the west, likely accompanied by a high-pressure system, signaling clear skies and stable weather.

It worked for me. The myth from the ancients prevailed, and the next day was calm and full of pale blue fall skies with just a bit of a nip in the air. I wove down Crooked Lake into and out of its weekday-named bays and came across Table Rock. Table Rock, as described by Beymer’s BWCA Guidebook, was a site of “an historic campsite where many a Voyageur rested while en route from Lake Superior to Lake Athabasca.”

If you haven’t seen Table Rock, it’s a rock that looks like a table that rests upon evenly placed rock legs. A dozen friends could sit around Table Rock just as dozens of Voyageurs likely had before. If you trust the ancient wisdom of online forums, at some point the Minnesota Historical Society contemplated moving the rock to the Twin Cities as an exhibit, and it broke. Or it was broken in two during a different move. There are also claims that the rock was lifted up by CCC crews using car jacks and placed upon its legs.

It was probably just glaciers that dropped the rock upon other rocks. But legends are legends and can get embellished over time.

I stopped at table rock and paddled a bit further before camping.

Morning on the Basswood River gave way to another beautiful day with a red sky at night the night before. A light wind created smooth ripples across the surface of the river.

I was lost within the paddle strokes and watching the water drip from my blade and keeping the bearing correct by watching my compass. Other than those activities, all the busy thoughts in my mind were cleared. I was as much the paddle and the drips and the compass heading as I was myself.

I looked up from my map and noticed something on the western side of the river. There was a cliff rising from the calm water. The cliff was covered with orange lichen, and it had an overhang. When traveling in the BWCAW, you see cliffs like this all the time. A boreal forest topped the cliff with birch intermingling with fir and spruce.

But something was out of place. At first, my mind couldn’t register what it was seeing because there wasn’t a canoe tied to shore. I hadn’t noticed anyone on the river with me.

But upon the top of this cliff was something. It was standing upright and looked like a man.

But…

It had horns.

Or was it antlers.

It was furry.

It was standing on the top of the cliff. The moment seemed to freeze in time, and I glanced at the slow drop of a water drip from my paddle. It hit the water, created a splash, then a ring.

When I looked back at the cliff, the thing was gone.

I paddled closer to the cliffs. Reddish faded pictographs covered the cliff’s surface. There was a fish in a net, birds, a moose smoking a pipe, a canoe with paddlers, Mishipeshu, and a Manitou with horns and the body of the man.

Before I arrived at the site, I didn’t know what I would find. At some point, I saw it marked on the map but wasn’t sure I was near it. Was there truth in the paintings, I wondered. Had someone in the past experienced the same vision as I had and painted their vision upon the walls of that cliff?

What did I see, I asked myself. Did I see anything, I wondered, as I doubted my own eyes.

I’m not sure.

According to an old idiom, the mind works in mysterious ways. I had previously read Furman’s Magic on the Rocks, which is a book about the pictographs found in canoe country. My mind could have subconsciously remembered what I read and projected that onto the cliff. Of the Basswood River pictographs, he wrote about and included a picture of the human figure with horns. What I remember seeing vaguely looked like that. It was a furry, human figure with horns.

My mind was also primed by the romantic outdoor writings about how the wilderness changes you, and if you are open to it, you will experience something akin to a mystical transformation or experience.

To think that we can explain everything seems naïve. I saw it so it had to be real, right?

I don’t know.

What I do know is that I canoed. That vision on the cliff lasted only a second, but every day on that trip I dipped my paddle, stroke after stroke, and watched the water drip off and reconnect with the lake.

Those moments were just as real and just as amazing.

That day, I know that I saw something standing on top of the cliff.

I know there were pictographs under that figure.

I know that I paddled there.

I know that I paddled on.

And on.

On my last day of the trip, I rose early to watch the sun paint an unsettled sky red. It looked like rain. I hurried to break camp, and not long after drops of rain started to ripple across the water. I paddled across South Fowl Lake to my first portage of the day. It was onto the Pigeon River.

I had never paddled the Pigeon River before, so I was excited to see it. The fall had been dry, and the river was boney in the rapids. I waded next to the river through the first rapid, pushing and pulling my canoe around boulders. I paddled areas deep enough to paddle. I portaged past Partridge Falls, a waterfall that plunged into a canyon.

It was mid-afternoon when I reached Fort Charlotte at the top of the Grand Portage, an eight-mile portage trail connecting the inland lakes to Lake Superior. I had never done this portage before, but I was soaked from the rain and wanted to reach the bottom and ride home. Instead of camping another night, I lifted my pack and canoe onto the shoulders and started the walk down the trail. After thirty minutes, I was tired. I set the canoe down and rested in the rain.

I repeated the rhythm of carrying and resting as I marched through the boreal forest. The walk took me past cedars so old and big that it would take several people to hug them. My boots splashed through puddles, and I couldn’t help but think back over the trip as I closed in on its ending.

I wondered about what I had seen on that cliff. I reflected on the red skies at night and the red skies in the morning. I had paddled the old Voyageur route. I had watched drips fall from my paddle rejoin the lake, again and again and again. I know I saw something, but maybe, in the end, all that mattered is to canoe.

Until next time

I hope you enjoyed this essay, albeit it was less about the photo and more about the things we experience when getting the photos.

Check out my 2026 Photo Workshops. It’s hard to believe that they are filling up already. Here’s the parting shot and I’ll see you again in two weeks.

Perhaps wear a GoPro on your head to record then you will know for sure what you think you saw was real or a vision. ;) Neat trip ... thanks for sharing.

Haha, I love this story! So full of mystery, but as you say, the really profound part is simply the journey and the act of canoeing.